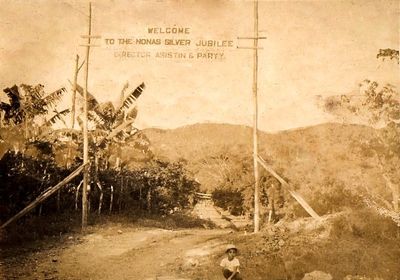

A Glimpse of NONAS

I was waitlisted for 23 days.

However, my determination was greater than the wall of ignorance and poverty.

My resolve won the approval of the Principal, but the Farm Manager was incited by the Principal’s unilateral acceptance. Not surprisingly, my grade in Fieldwork under the Farm Manager’s supervision was the lowest among the seven subjects of our Secondary Agricultural Curriculum. The Farm Manager’s indifference only challenged me to strive and study harder. I was motivated to take the lead in almost all our class activities.

There were eight members in our group No. 137, but only five finished the four-year curriculum. Three students dropped out. Our group had 1.5 hectares of farmland to plant corn, rice, fruits, and vegetables. We also raised poultry and swine, chicken eggs, and chicken meat. Any extra produce went to the weekly ration for the insiders, the first and fourth-year students. The proceeds of our farm products were kept in the student bank, managed by the cashier. We were not allowed to withdraw our savings unless for meritorious reason.

The Four-Year Secondary Agricultural Terminal Curriculum was made up of about 40% Academic Classes and 60% Fieldwork. The six-day work week was divided into 2-3 days in Academic Classes and 3-4 days spent in Fieldwork. The Fieldwork activities included actual farming, clearing the virgin forest, and planting the cleared area with rice, corn, root crops, and vegetables. The idea was that the students could produce whatever food materials they needed to survive. The mean objective of the curriculum for the male students was to prepare them for proficiency in farming.

There were two categories of male students in NONAS. The insiders were the first and fourth-year students who were housed in the dormitory and given a food ration. The insiders were to do the menial jobs, caring and maintaining different school projects such as the sugar cane farm, rice and corn production, poultry and swine raising, goats, sheep, and cattle care, etc.

The first-year students were just beginning to cultivate their farms and therefore did not have any produce yet to support their daily food. The fourth-year students were also provided with a food ration because they were required to do more jobs on top of the Fieldwork. They were expected to know the basic skills in farming agriculture, as well as simple office work.

The other category of male students were the independent farmers, made up of the second and third-year students. As the term suggested, they were encouraged to build their cottages on their farms and live independently. At this time, they were expected to have some rice and/or corn products, vegetables, and fruits for their food. They also raised chicken and swine.

To give emphasis and meaning to the secondary agricultural curriculum, the boys organized themselves into a student organization named Future Farmers of the Philippines (FFP) with the close instruction and advice of their agriculture teachers. This is a unique organization wherein the boys were taught the art of public speaking in addition to their regular lessons in agricultural art and science. This elite organization were made up of only boys enrolled in agricultural fishery and trade schools in the Philippines. They conducted their meetings in an orderly manner by adopting Roberts’ Rules of Order and held annual, local, regional, and national conventions simultaneously with their female counterpart, the Future Agricultural Homemakers of the Philippines (FAHP). At one point, the local FFP chapter President of the Negros Occidental National Agricultural School was sent to the United States of America to attend the National Convention of the Future Farmers of America upon their invitation.

In the 1951-1952 school year, NONAS added another Secondary Curriculum in Home-making for the girls. This was the first time that NONAS offered this Secondary Agricultural Home-making that included dressmaking, cooking, and agricultural arts with the boys. The girls were called the Future Agricultural Homemakers and formed their own organization, the FAHP. The FAHP also held annual National Conventions wherein the knowledge and skills learned in the classrooms and in the fields were contested. The FAHP also had their knowledge and skills contests in basic agricultural science and arts, enriched by home economics, cooking, dressmaking, childcare, care for the sick, etc.

The girls, unlike the boys, were given free dormitory accommodation in cottages and provided with free food ration. They were classified as all insiders. The girls were not required to stay on the farm like the boys. They had lighter work activities during the Fieldwork period, in addition to their Homemaking lessons and activities. The girls underwent lighter Fieldwork activities such as raising rice, corn, root-crops, vegetables, fruits, and flowers in smaller land area. They raised poultry swine, ducks, geese, etc. In exchange for the free ration, dormitory accommodation, and other privileges, the girls worked menial jobs such as simple office work and maintained small school projects, plant nurseries, residential yards, official offices, the library, and school clinic.