My Time on the Farm

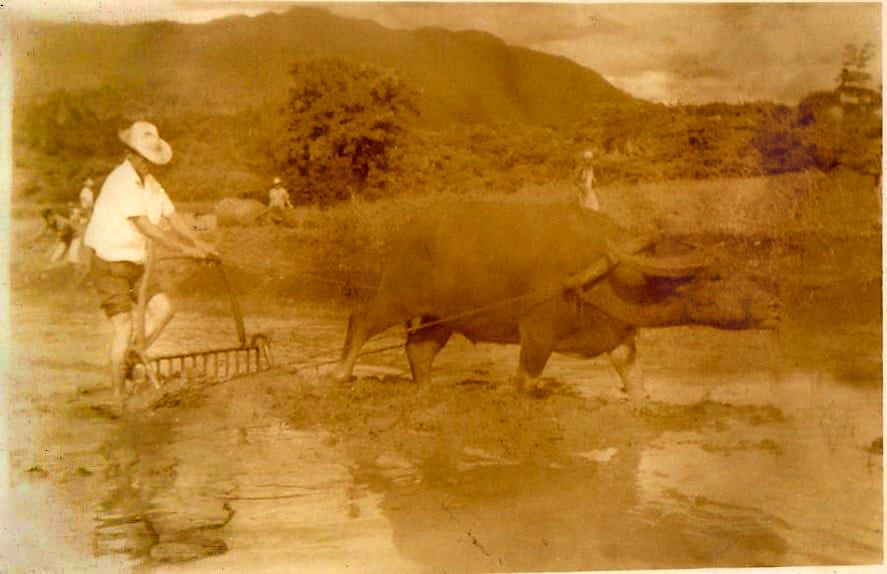

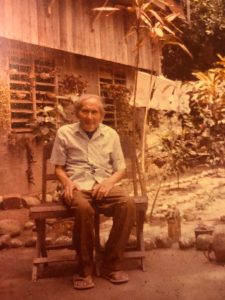

At six years old, I was made to pasture 18 heads of big carabaos (water buffalos) by our grandfather, JULIAN DECHAVEZ (referred to as “Lolo Julian”). He was the patriarch of the family, and we respected him more than our father.

My herding responsibility kept me from my early primary education. In fact, my younger sister finished first grade before I did. These carabaos were the collective source of farming power on the farm. These beasts were relied on for plowing, harrowing, hauling, and pulling for transportation. Lolo Julian had about ten hectares of rice land, and these carabaos were the labor in cultivating his land. I finally attended my primary elementary education at 11 years old but continued to often miss school days due to my usual family assignment of herding, peddling, and/or bartering.

I attended my primary and elementary grades barefoot with old clothes shared by my cousin ANECITO ‘SITOY’ DECHAVEZ. Sitoy and I were close cousins. We were classmates throughout elementary, graduating with honors. After my elementary graduation, I was directed again by our grandfather to work with him on a 7-hectare farm. The land needed to be cleared first before it could be made productive.

This farm was located in the next town of Sagay, about 25 kilometers from our place in Cadiz. Since this was a pioneering project, our grandfather brought 12 well-trained carabaos to this farm located in a remote barrio called Campo Santiago. It took us 18 hours to shepherd the 12 carabaos. We left our Barrio Luna as early as 4 o’clock in the morning and arrived at Campo Santiago as late as 10 in the evening. Sitoy and I were committed to helping our grandfather realize his ambitious plan of clearing the area and making it productive. At times, Sitoy and I felt lonely while staying in the partly forested, remote farm, but we could not afford to disappoint our dear grandfather. During a short break, I asked my grandfather’s permission to visit home.

When I arrived back home, our eldest sister Magdalena handed me a letter from Aquilino Villanueva “Manong Aqui.” He was studying to the south of us at the Negros Occidental National Agriculture School (NONAS). He invited me to follow him and study at the same school. My family did not have the means to accept the invitation. I, myself, had no means other than my burning ambition to study, even if that said ambition could cost me everything.

Magdalena had a young female pig she planned to sow for future profits, but due to my desire to study, I was able to convince her to sell her only pig to help me go to school at NONAS. My very accommodating sister reluctantly sold her pig for a humble 15.00 pesos and gave all the proceeds towards my education.

The invitation letter gave me strict instruction. The first was a requirement that all applicants for the first year must undergo a two-week “try out”. This was a skills test of manual jobs such as clearing a virgin forest, constructing a road, fencing the cattle and carabao ranch, and caring for and feeding livestock, pigs, or hogs, poultry, goats and horses. Fortunately, I still had one month until the start of the try-out. The month gave me an opportunity to earn more money harvesting sugarcane in the feudalistic hacienda. I harvested sugarcane cuttings and pilings and loaded cut sugarcanes in the ‘bagon’ or flat cart that was pulled by a locomotive train and brought to the sugar mill. My daily wage as a sugarcane laborer was only .70 centavos or P21.00 per month. When the NONAS try-out started, I had earned an additional 21.00 pesos to add to my sister’s contribution.

As I was preparing my first trip to NONAS in Kabankalan, Negros Occidental, I felt like I was walking on air from my excitement, anticipation, and sense of accomplishment.

I was the master of my own destiny.